"actions speak louder than words..."

The Italian revolutionary Pisacane is considered an early proponent of propaganda of the deed, arguing that "ideas spring from deeds and not the other way around... The use of the bayonet in Milan has produced a more effective propaganda than a thousand books." During the historical period known as Risorgimento, Pisacane represented the extreme left, and as a follower of French philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon introduced Anarchism in Italy. His essays, titled Saggi and Testamento Politico, were published posthumously in France.

For ARTIVIST : creative there is a process involved with the entire concept of 'propaganda of the deed' that considers:

to act & develop upon action requires thought & preparation of resources;

to maintain impact & allow the deed to evolve;

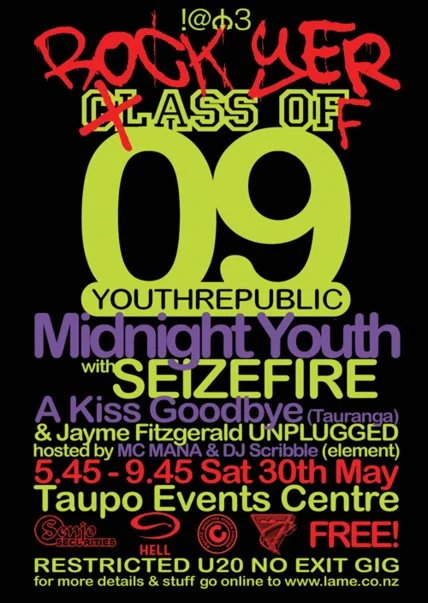

identification & establishment of 'cells' or groups that can operate with autonomy but with some defined organisation - fan groups.

Mutualism

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought that originates in the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who envisioned a society where each person might possess a means of production, either individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent amounts of labor in the free market. Integral to the scheme was the establishment of a mutual-credit bank that would lend to producers at a minimal interest rate, just high enough to cover administration. Mutualism is based on a labor theory of value that holds that when labor or its product is sold, in exchange, it ought to receive goods or services embodying "the amount of labor necessary to produce an article of exactly similar and equal utility".

Mutualist economics

The major tenets of mutualism are free association, mutualist credit, contract (or federation/confederation), and gradualism (or dual-power). Mutualism is often described by its proponents as advocating an "anti-capitalist free market".

Contemporary mutualist author Kevin Carson holds that capitalism has been founded on "an act of robbery as massive as feudalism," and argues that capitalism could not exist in the absence of a state. He says it is state intervention that distinguishes capitalism from the free market". He does not define capitalism in the idealized sense, but says that when he talks about "capitalism" he is referring to what he calls "actually existing capitalism." He believes the term "laissez-faire capitalism" is an oxymoron because capitalism, he argues, is "organization of society, incorporating elements of tax, usury, landlordism, and tariff, which thus denies theFree Market while pretending to exemplify it". However, he says he has no quarrel with anarcho-capitalists who use the term "laissez-faire capitalism" and distinguish it from "actually existing capitalism." He says he has deliberately chosen to resurrect an old definition of the term. Carson argues the centralization of wealth into a class hierarchy is due to state intervention to protect the ruling class, by using a money monopoly, granting patents and subsidies to corporations, imposing discriminatory taxation, and intervening militarily to gain access to international markets. Carson’s thesis is that an authentic free market economy would not be capitalism as the separation of labor from ownership and the subordination of labor to capital would be impossible, bringing a class-less society where people could easily choose between working as a freelancer, working for a fair wage, taking part of a cooperative, or being an entrepreneur. He notes, as did Tucker before him, that a mutualist free market system would involve significantly different property rights than capitalism is based on, particularly in terms of land and intellectual property.

Free Association

Mutualists argue that association is only necessary where there is an organic combination of forces. For instance, an operation that requires specialization and many different workers performing their individual tasks to complete a unified product, i.e., a factory. In this situation, workers are inherently dependent on each other – and without association they are related as subordinate and superior, master and wage-slave.

An operation that can be performed by an individual without the help of specialized workers does not require association. Proudhon argued that peasants do not require societal form, and only feigned association for the purposes of solidarity in abolishing rents, buying clubs, etc. He recognized that their work is inherently sovereign and free. In commenting on the degree of association that is preferable Proudhon said:

"In cases in which production requires great division of labour, it is necessary to form an ASSOCIATION among the workers... because without that they would remain isolated as subordinates and superiors, and there would ensue two industrial castes of masters and wage workers, which is repugnant in a free and democratic society. But where the product can be obtained by the action of an individual or a family... there is no opportunity for association."

For Proudhon, mutualism involved creating "industrial democracy," a system where workplaces would be "handed over to democratically organised workers' associations . . . We want these associations to be models for agriculture, industry and trade, the pioneering core of that vast federation of companies and societies woven into the common cloth of the democratic social Republic." He urged "workers to form themselves into democratic societies, with equal conditions for all members, on pain of a relapse into feudalism." This would result in "Capitalistic and proprietary exploitation, stopped everywhere, the wage system abolished, equal and just exchange guaranteed." Workers would no longer sell their labour to a capitalist but rather work for themselves in co-operatives.

As Robert Graham notes, "Proudhon's market socialism is indissolubly linked to his notions of industry democracy and workers' self-management." K. Steven Vincent notes in his in-depth analysis of this aspect of Proudhon's ideas that "Proudhon consistently advanced a program of industrial democracy which would return control and direction of the economy to the workers." For Proudhon, "...strong workers' associations . . . would enable the workers to determine jointly by election how the enterprise was to be directed and operated on a day-to-day basis."

Mutual Credit

Mutualists argue that free banking should be taken back by the people to establish systems of free credit. They contend that banks have a monopoly on credit, just as capitalists have a monopoly on land. Banks are essentially creating money by lending out deposits that do not actually belong to them, then charging interest on the difference. Mutualists argue that by establishing a democratically run mutual bank or credit union, it would be possible to issue free credit so that money could be created for the benefit of the participants rather than for the benefit of the bankers. Individualist anarchists noted for their detailed views on mutualist banking include Proudhon, William B. Greene, and Lysander Spooner.

Some modern forms of mutual credit are LETS and the Ripple monetary system project.

In a session of the French legislature, Proudhon proposed a government-imposed income tax to fund his mutual banking scheme, with some tax brackets reaching as high as 33⅓ percent and 50 percent, which was turned down by the legislature. This income tax Proudhon proposed to fund his bank was to be levied on rents, interest, debts, and salaries. Specifically, Proudhon's proposed law would have required all capitalists and stockholders to disburse one sixth of their income to their tenants and debtors, and another sixth to the national treasury to fund the bank. This scheme was vehemently objected to by others in the legislature, including Frédéric Bastiat; the reason given for the income tax's rejection was that it would result in economic ruin and that it violated "the right of property." In his debates with Bastiat, Proudhon did once propose funding a national bank with a voluntary tax of 1%. Proudhon also argued for the abolition of all taxes.

Contract & Federation

Mutualism holds that producers should exchange their goods at cost-value using systems of "contract." While Proudhon's early definitions of cost-value were based on fixed assumptions about the value of labor-hours, he later redefined cost-value to include other factors such as the intensity of labor, the nature of the work involved, etc. He also expanded his notions of "contract" into expanded notions of "federation." As Proudhon argued,

“"I have shown the contractor, at the birth of industry, negotiating on equal terms with his comrades, who have since become his workmen. It is plain, in fact, that this original equality was bound to disappear through the advantageous position of the master and the dependent position of the wage-workers. In vain does the law assure the right of each to enterprise . . . When an establishment has had leisure to develop itself, enlarge its foundations, ballast itself with capital, and assure itself a body of patrons, what can a workman do against a power so superior?"”

Gradualism & dual-power

Beneath the governmental machinery, in the shadow of political institutions, out of the sight of statesmen and priests, society is producing its own organism, slowly and silently; and constructing a new order, the expression of its vitality and autonomy...

Proudhon noted that the shock of the French Revolution failed the people, and was instead interested in a federation of worker cooperations that could use mutualist credit to gradually expand and take control of industry. This is similar to economic models based on worker cooperatives today, such as the Mondragón Cooperative Corporation in Spain and NoBAWC in San Francisco.

Clandestine Cell Systems

The operational cells need to have continuous internal communication; there is a commander, who may be in touch with infrastructure cells or, less likely from a security standpoint with the core group.

Al-Qaeda's approach, which even differs from that of earlier covert paramilitary organizations, may be very viable for their goals:

Cells are redundant and distributed, making them difficult to ‘roll up’;

Cells are coordinated, not under "command & control"—this autonomy and local control makes them flexible, and enhances security;

Trust and comcon internally to the cell provide redundancy of potential command (a failure of Palestinian operations in the past), and well as a shared knowledge base (which may mean, over time, that ‘cross training’ emerges inside a cell, providing redundancy of most critical skills and knowledge).